Big Picture Farm, What's Your 'Local'?

“For the farmer, food is necessarily the product of labor,” writes Jim Corbett in his book Goatwalking. “For the herder, food is a gift, eternally regenerating itself.”

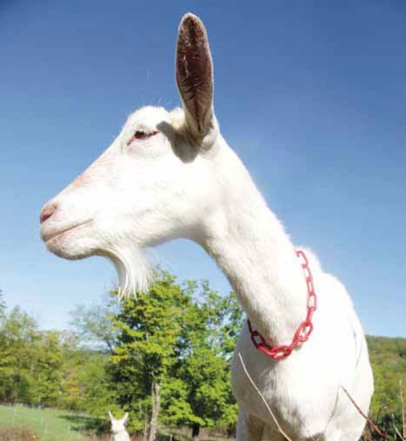

As dairy farmers, we know that these statements aren’t mutually exclusive. The labor is real—we must milk our goats twice a day, take down and put up new pastures, trim hooves, mow fields, muck shit, schlep water, CLEAN everything … ad infinitum.

But the labor is rewarding because the goats match our labor with their own—by supplying us with creamy, earthysweet, delicious whole milk each and every day.

And these aren’t just any goats. These are individual, uniquely expressive, deeply emotive, often ridiculous, beautiful, loving creatures-in-this-world! There’s overly protective Cicada, head-butting our neighbor’s dog.

Or retired Gertrude, who fiends for a head scratch. Eva, the tree climber. Carmine, the conversationalist. Junebug, the diva. Root Beer, the hand-biter. Orion, the wizened queen. Twig, the mischief. Manhattan, the tree-toppler.

Take, for instance, Fern, who won’t cross a stream no matter what—even when it’s a slow trickle and several sturdy stepping-stones path the way to the other side. Not Fern. She’ll remain on the near bank picking at limb ends, lonesoming the occasional howl at the rest of the herd now off in the distance.

For us, what makes food “local” is when the context surrounding its production is inseparable from the product itself. Each caramel that we produce comes from a place, a specific place, and is made from the milk of a specific animal, eating specific flowers and leaves and plants at a specific time of year. And what’s exciting for us as farmers and food producers is taking a proactive stance on SHARING this context with our customers.

A requisite for “local” food should be that it arrives on our plate accompanied by an intimate knowledge of its production.

Even “organic”— which was once associated with local, small-farm production—increasingly has lost appeal because of the ease with which large companies can achieve “organic” status and lean on it in lieu of providing real, intimate knowledge to a customer.

We need only look at the current GMO labeling debate. At the heart of it is the simple desire for transparency. Knowing what’s in the food and where it comes from is integral to our emotionalnutritional analysis. Sourcing that “living” knowledge might be hard work, but the need to do so is becoming more and more pressing, for that knowledge deepens our experience of taste—renders it an eternally regenerating gift.

At Big Picture Farm, we want you to know that Fern’s milk went into the caramel you’re now placing in your mouth, so that—in addition to the foreground taste, that creamy and lingering southern Vermont tang—you’re granted access to the background taste: her breakfast of striped maple, the season’s first wild baby strawberries and justblossoming vetch. That uncrossable stream.

—Lucas Farrell & Louisa Conrad

Big Picture Farm, Townshend VT

BigPictureFarm.com