Grounded in Stone

“I guess I inherited some of my dad’s engineering genes because I’ve always been curious about building things. For this project, I taught myself how to weld, machine, and cut stone.” –Andrew Heyn

PHOTO: MARIA BUTEUX READE

In 2014, Andrew Heyn had been running Elmore Mountain Bread for a decade with his wife, Blair Marvin, and the couple had grown increasingly interested in milling their own flour. A baker friend from Asheville, North Carolina convinced Andrew that he should try to build his own mill using natural granite stones. Andrew, a hands-on polymath, decided he was up for a new challenge and immersed himself in research. His primary source was Practical Milling by B.W. Dedrick, a dense tome from 1924. He also turned to the Society for the Preservation of Old Mills that had reprinted many works about milling technology from the 19th century.

“I guess I inherited some of my dad’s engineering genes because I’ve always been curious about building things. For this project, I taught myself how to weld, machine, and cut stone.”

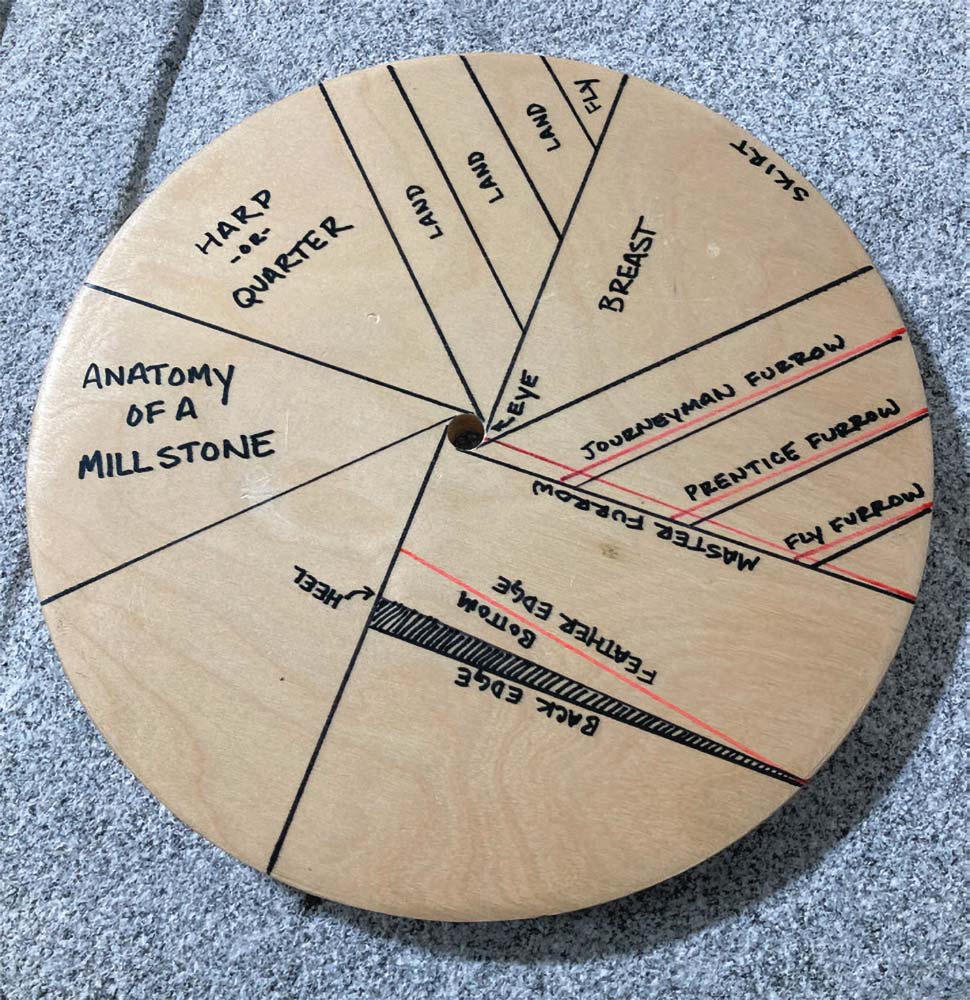

A New American Stone Mill consists of two 5-inch-thick granite stones—the bed stone and the runner stone—positioned atop one another. Depending on the circumference, each disc weighs between 300 and 1,400 pounds. Whole grain falls from the hopper above into a hole cut in the center of the runner stone that spins at 27mph just thousandths of an inch above the stationary bed stone, crushing the grains into flour that channels through the millstones’ cut grooves to the perimeter where it’s funneled through a chute into a bin below. Freshly milled stone-ground flour.

Andrew sold his first mill in 2015, thus launching New American Stone Mills, now based in a spacious industrial facility in Morrisville. Andrew and his small team fabricate the steel frame that supports the stones, motor, and other apparatus. Luke Gellatly, Andrew’s right-hand man since 2018, designed and created the mill’s popular sifter attachment. They also carve the grooves, or furrows, into the flat granite surface, known as the lands. Millstones come in three sizes: 26, 40, and 48 inches. The planed granite discs come from Granite Importers, a third-generation stonecutter in Barre. Natural gray granite is the stone of choice thanks to its fine grain, homogenous crystal texture, density, and durability. Its large thermal mass also keeps the stones cool despite the heat of friction from the milling process.

Andrew Heyn dressing, or cutting grooved furrows into, the surface of a granite millstone. PHOTO: BLAIR MARVIN

What’s special about stone-ground flour? All parts of the whole grain—bran (the outer coat that contains most of the fiber), germ (contains vitamins and healthy fats), and endosperm (the tender interior that contains proteins and starches) get crushed together, which means the oils, vitamins, and fiber are ground into the endosperm, creating a more flavorful, aromatic, and healthy final product. Whereas refined white flour has had the germ and bran removed, which results in diminished nutritional value. Many bakers prefer to use flour from freshly milled grain because those qualities naturally imbue their baked goods with a nutty richness and pleasant texture. Depending on how they adjust their mill and blend their flour, millers can produce a fine, sifted all-purpose flour that contains the germ and fine bran or a whole wheat flour that contains all the bran.

Andrew and Blair also own Elmore Mountain Bread, a wood-fired micro bakery based at their home in the hills above Elmore. Once Andrew built their mill, the couple began to transition from using organic white flour from Quebec to using 100 percent stoneground organic wheat from Vermont farms.

New American Stone Mills and Elmore Mountain Bread have become a replicable model. “Our goal is to build a community of bakers committed to using local grains and fresh flour to make products for their community, and thus ensuring a better, healthy, local food system,” Andrew says.

Andrew sees each mill as a tool that gives independence and control to farmers who grow grains and bakers who want to mill their own flour. Farmers can mill their own grain and sell directly to consumers, getting more value for their products rather than selling to a distant commodity market. Bakers can support their local or regional grain economy and create with the freshest milled flour.

Blair Marvin scooping Redeemer wheat from Nitty Gritty Grain Company into her mill at Elmore Mountain Bread. COURTESY ELMORE MOUNTAIN BREAD

Demand for Andrew’s stone mills continues to increase, thanks to consumers’ own interest in supporting a local grain economy of farmers, millers, and bakers. Since 2015, 225 New American Stone Mills have been fabricated, shipped, and installed across the United States (39 states, including 9 right here in Vermont), Canada, Europe, Great Britain, and Australia. Each mill comes with lifetime service from Andrew who provides training, technical support, and guidance on how to maintain the mill and dress (recondition) the stones. “These mills will outlast the miller,” he likes to say.

Pretty cool that the United States’ foremost authority on how to build, fix, and maintain stone mills lives right here in northern Vermont. And that this soft-spoken millwright named Andrew Heyn stays so grounded, much like the granite quarried 35 miles south in Barre.

Andrew sees each mill as a tool that gives independence and control to farmers who grow grains and bakers who want to mill their own flour.

Luke Gellatly (left) and Andrew Heyn proudly show off a granite millstone in their Morrisville facility. PHOTO: MARIA BUTEUX READE