Deirdre Heekin: Vermont Garagista with a European Sensibility

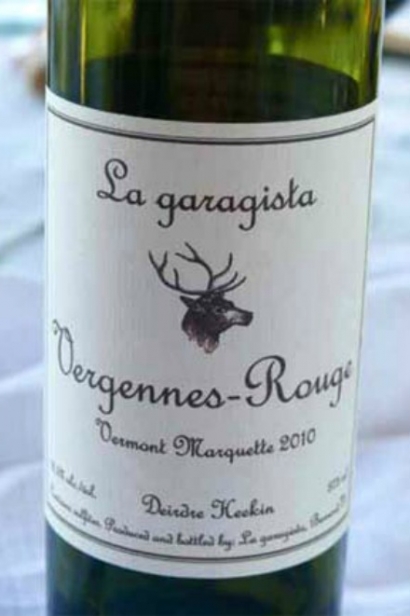

It was a soft August day, a light breeze dappling the vineyard in the hills of Barnard, Vermont. Deirdre Heekin reached across her farmhouse table to pour me a glass of her 2011 Marquette Vergennes Rouge, the second vintage of this wine.

I swirled and sniffed. Limpid berry pink with a fuchsia rim, it yielded aromas of mint, fennel and faint floral cherry. Peppery on the palate, it had bracing acidity and a short, clean finish, all hallmarks of a cool-climate red. “This wine is as old-fashioned as possible,” she said, swirling her own glass. “All wild yeast, no de-acidification, no chaptalization, no funny business— nothing.”

Then she poured the 2010 vintage, a warmer year. It was a bigger wine, with more pronounced cherry fruit and hints of eucalyptus above the mint. But this was still not your typical American red.

“My wines definitely are higher in acidity, and I think they’re actually better with food,” Deirdre said. “I don’t look to California as a model. Aesthetically, that’s not the direction I’d like to go in. Instead, I’m looking to Austria, Germany, Northern Italy and parts of France.” Wines from those cooler regions tend to be savory with a pronounced mineral aspect, rather than fruity and soft. They’re also meant to be enjoyed as part of a meal—true gastronomy wines.

Deirdre should know. An experienced restaurateur and sommelier, she and her husband, Caleb Barber, run Osteria Pane e Salute, a flawlessly authentic Italian restaurant in Woodstock, Vermont. Their seasonal menu features ingredients sourced from Vermont producers, including the couple’s own gardens. Deirdre’s wine list is a trove of rare indigenous Italian varieties.

But why make wine herself?

“It started as an educational project for my work as a wine director,” she said. “I knew intellectually how wine was made, but there were pieces missing in my view of the process. What is fermentation? What is malolactic? I needed to know what making wine felt like.”

So about six years ago, she began traveling in France and Italy, muddying her boots in the vineyards alongside organic and Biodynamic winegrowers. She also began to connect with Vermont winemakers who were making wine from local fruit. Emboldened, she bought some grapes and made her own wine, garagiste style.

Then in the summer of 2008, she and Caleb visited Lincoln Peak Vineyard in New Haven, Vermont. It was an epiphany: serious wine, grown right here in Vermont. They left that day with vine cuttings to plant on their own two-acre parcel. La Garagista was born.

From that first small planting of 50 vines, their vineyard has grown to 1,200, mostly Marquette and La Crescent, plus Riesling, Blaufränkisch and Frontenac Blanc, Gris and Noir. In 2011, she produced her first tiny vintage using fruit from her own land. By 2013, production will be in full swing.

In the meantime, she has made wine from grapes grown at Mina Brothers Vineyard in Vergennes, Vermont. The learning curve has been steep. “All those guys in France, in Italy—they’ve got generations behind them, and a community in which they can compare notes,” Deirdre said. In Vermont, viticulture’s still new. Snow Farm in South Hero was the first to plant, in 1996, but the state still has only 23 licensed wineries, compared to 3,400 in California, for example.

“Everybody’s vineyard is an experiment. We can share information, but nobody has definitive answers. I’m learning as I go along.” Deirdre farms organically, attending to vineyard soil and vine health using Biodynamic preparations and composts, and covercropping with plants like buckwheat. She harvests manually, footstomps the fruit, relies on native yeasts for fermentation and ages the wines in glass demi-johns instead of oak to preserve their purity and freshness. She does conduct some bâtonnage, or lees stirring, to impart savoryness and a creamy texture, and uses a tiny amount of sulfur at bottling to prevent spoilage. But these are minimal interventions with a long tradition in European winemaking. She shuns any modulations of a wine’s acidity, sweetness, alcohol or color, preferring to respond intuitively to what the wine needs, rather than transform it into something else, something more mainstream.

Her 2011 Vinu Jancu is a case in point. The name means “orange wine” in an old Sicilian dialect. This style is made by fermenting white grapes on their skins, imparting flavor compounds and tingeing the wine a salmon color. It’s a centuries-old process, but you’re not likely to find these wines on supermarket shelves.

Deirdre chose this approach for her white after tasting orange wines from Georgia, Slovenia and Friuli—also cool growing regions. “I loved each of them for their incredible texture and finish, but it was the aromatics that blew me away. They reminded me of what I was starting to experience in my own Vergennes Blanc. I felt this would be an interesting way to approach the La Crescent grape.”

She poured me a taste. The wine was a pale burnished peach color. Honeyed aromas of spring blossoms wafted over nutty, yeasty notes with sherry-like oxidation. Fully dry with great acidity, the wine had an enchanting texture and haunting flavor. She made only about 20 gallons of this wine, bottling it in 375ml glass, which makes it seem even more precious. “It may be our signature wine,” Deirdre said, “and one of our biggest triumphs to date.”

But her greatest excitement still lies in the learning process. “Really, my biggest triumph has been not messing around too much with the wine. Wine is a living thing, and wants to express itself in a particular way. These wines are teaching me to make wine in a very classic, hands-off style, so that terroir can come forth,” she said. “There is a lot to learn.”

FRENCH-AMERICAN HYBRID GRAPES

Vermont wine: The difference isn’t just in our soil and climate— it’s in the grapes.

European grapes like Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay aren’t hardy in regions like ours that can hit –35°F. Many Vermont winegrowers have planted French-American hybrid grapes, newer crossings that blend the cold-hardiness of indigenous North American varieties, particularly Vitis riparia, with the fruit character of the European grape, Vitis vinifera.

The University of Minnesota’s wine grape program, established in the mid-1980s, has produced several cold-hardy varieties now in production in Vermont, including Frontenac, Frontenac Gris, La Crescent and Marquette. Other hybrids common here include white Seyval Blanc and Traminette and red Baco Noir and Marechal Foch.

Wines made from these hybrids are somewhat akin to their European progenitors, especially aromatically. But they can also be more acidic, less tannic and lower in alcohol, which makes them challenging to wine drinkers accustomed to riper, more fruit-driven styles.

So, to create a commercially viable product more approachable to American palates, some cold-climate winemakers tinker with their wines to soften, de-acidify or add structure. Others take a hands-off approach, preferring to let the soil, grape and vintage speak, and to produce a wine expressive of the place it’s grown— its terroir.