Deirdre Heekin, La Garagista, Barnard

While Deirdre Heekin and her husband, Caleb Barber, were living in Italy, they fell in love with the fresh, young wines they enjoyed with their meals. Deirdre continued to travel back to Europe from Vermont to visit the vineyards and to meet the makers whose wines she offered at Osteria Pane e Salute, the acclaimed Woodstock restaurant she and Caleb shepherded from 1996 to 2017.

Meanwhile, at their farm in the Barnard hills, Deirdre began to make wine in 5-gallon buckets to better understand how pure, crushed fruit transformed into refreshing, clean wine through the magic of fermentation. On a hot July afternoon in 2007, Deirdre and Caleb planted 100 vines of cold-climate grapes they had just bought after a visit with Chris Granstrom at Lincoln Peak Vineyard, thus establishing what would evolve into Domaine La Garagista, producer of Vermont’s first organically grown natural wines.

Caleb Barber and Deirdre Heekin in the doorway of La Garagista‘s tasting room at their farm in Barnard. PHOTO KATIE LENHART PHOTOGRAPHY

Deirdre Heekin gently tends her crushed grapes. PHOTO KATIE LENHART PHOTOGRAPHY

“We saw a world of possibilities in Vermont wine and we wanted to embrace those opportunities,” Deirdre explains. “Lincoln Peak, Shelburne Vineyards, and Boyden Winery were producing wines that showed great potential using cold-climate grapes.” Inspired, they started tasting every Vermont wine they could.

Most people think that wine is made in the cellar. Deirdre firmly believes that wine is grown in the field. However, no one was growing grapes organically at the time, the only way Deirdre and Caleb would farm, so they bucked convention and continued to plant and tend these cold-climate, hardy grapes according to their values and to produce unique natural wines that brought national attention.

What distinguishes natural wine? Grapes are farmed using organic, biodynamic, or regenerative practices. After the hand-harvested fruit is crushed (often by foot-stomping, or pigéage) and pressed, activating the native yeast on the skins to kick-start fermentation, the resulting juice is left to evolve into its best self. Nothing is filtered, no chemicals added. Later, the winemakers bottle their wines as single varieties or create unique, small-batch blends. Natural wines can be anything: still or pét-nat (pétillant natural, or naturally sparkling), oxidative, or fresh and bright.

(left) CAPTION Cold-hardy Frontenac Blanc grapes flourish in Vermont. (right) CAPTION Ripening grapes await the September harvest. PHOTO KATIE LENHART PHOTOGRAPHY

Pét-nat’s pinpoint bubbles taste crisp and creamy, refreshing to the palate, perfect to pair with almost any food. Both still and sparkling, these wines captivate with each sip, the antithesis of commercial glug loaded with additives. You feel good while drinking them—and after—with no sulfite-induced throb.

Deirdre and Caleb now farm 12 acres of vines spread across five different parcels: two in Barnard, two in the Champlain Valley, and one in Bridgewater. They also tend an orchard of apple, pear, plum, peach, and sour cherry trees whose fruit is used in various co-ferments. All wines are made at La Garagista, although the team is setting up a small production facility on their West Addison property to make room for their growth. Their five vineyards are planted to different combinations of these varieties: Marquette, Frontenac Noir, St. Croix La Crescent, Frontenac Blanc, Frontenac Gris, Brianna, and Louise Swenson. These cold-climate hybrid vines come from Andy and India Farmer at Northeastern Vine Supply in West Pawlet, Vermont.

To the untrained eye, it’s hard to distinguish the vines from the tangle of surrounding plants among the trellised rows. And that’s exactly how Deirdre likes it. “We let the native plants emerge so we can understand what’s happening in the soil. Native plants provide a wealth of information and help us determine which biodynamic plant-based teas to steep and spray to manage pests and strengthen the plants’ immunity. I believe plant competition is healthy for hybrid varieties. The vines must work harder to establish deep roots rather than concentrate on upward growth. The strongest, most productive vines have the deepest root structures and are able to flourish more despite challenges caused by extreme weather.”

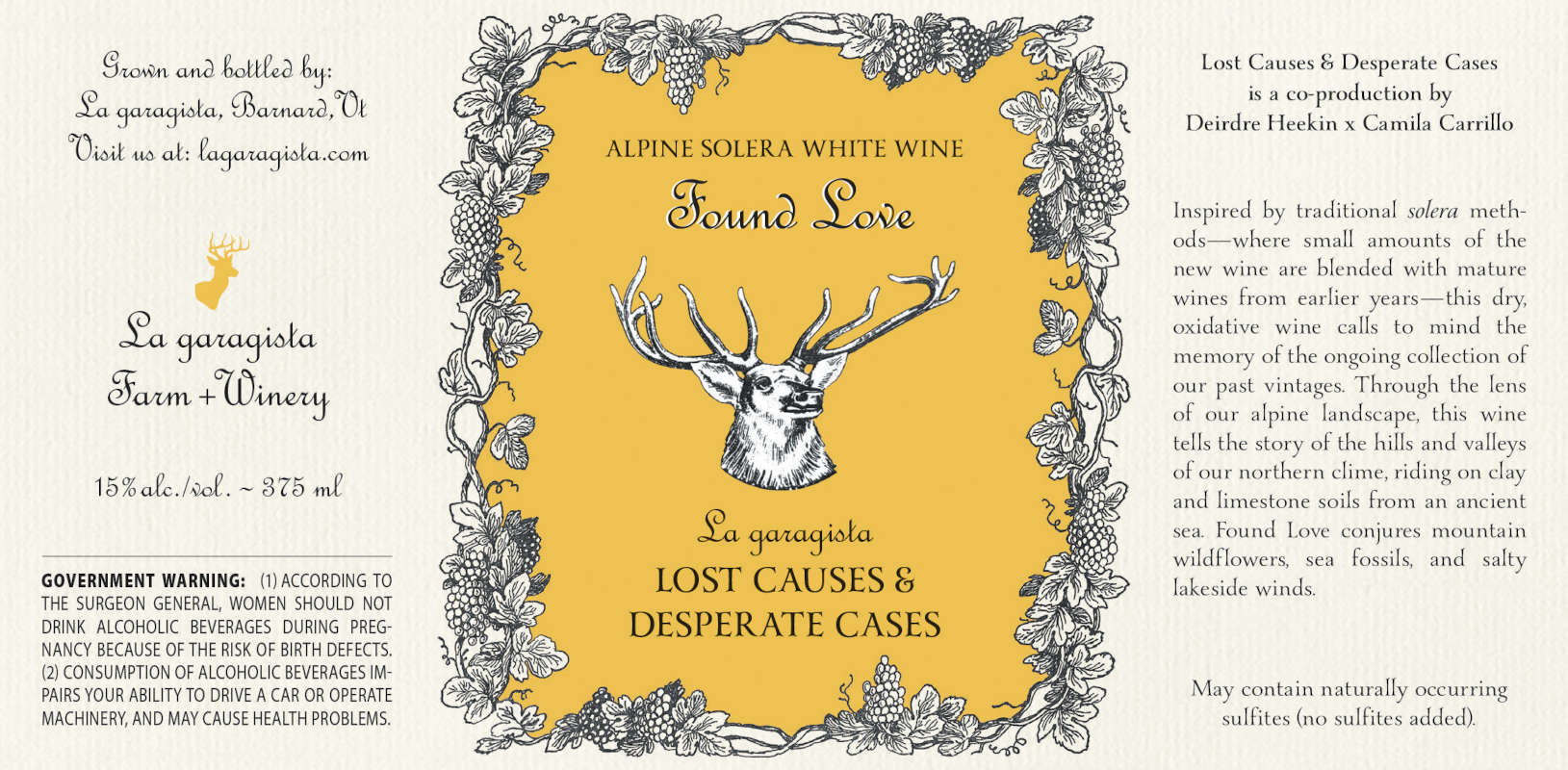

La Garagista was named one of Wine & Spirits magazine international “Top 100 Wineries 2023,” the first time a Vermont winery has been recognized; they were also nominated several times for James Beard awards. Deirdre produces an average of 35 different cuvées including several co-fermented ciders. Among the popular pét-nats are the three sisters (white, red, rosé) of the Ci Confonde series and Grace & Favour. Still wines include flagship Damejeanne, a fruity and bright Vermont red, and Harlots & Ruffians, a playful white field blend. Another flagship, Vinu Jancu, is a skin-macerated white fermented in open vats and cycled through a massive amphora made of Champlain Basin clays by a Montreal ceramicist.

Domaine La Garagista launched The Forêt Wine Guild, a community-supported agriculture (CSA) wine club in August 2024. Wines can be shipped to 37 states or picked up at the farm. The farm also hosts frequent weekend pop-ups in the garden and tasting room; check Instagram or sign up for the newsletter for further information.

As the late afternoon sun descended behind Mount Hunger, throwing shadows across the verdant, fruit-laden vines, Deirdre paused to reflect. “When we started, no one else was farming cold-climate grapes organically so there was no knowledge base. People assumed these hybrid varieties couldn’t be cultivated organically in this part of the country because of the humidity and rain. But I knew of similar regions in France and Italy that were doing it so I trusted we could do the same.”

That early lack of common knowledge forged Deirdre’s commitment to freely share whatever she knows with other farmers, including the apprentices and partners who comprise Gruppo Garagista. “We encourage our apprentices to start making wines and co-fermented ciders here. Sharing this space, equipment, knowledge, and labor benefits all of us. It’s about building an open community of collaboration. Even though many of us grow the same varieties of grapes, each of our wines is distinctive so there’s room for all of us.” And this rising tide of natural wines has made Vermont a recognized region for increasingly exceptional products.

PHOTO KATIE LENHART PHOTOGRAPHY

Hungry for more?

Read one of Deirdre Heekin’s beautifully crafted memoirs.

In Late Winter We Ate Pears: A Year of Hunger and Love

Libation: A Bitter Alchemy

An Unlikely Vineyard: The Education of a Farmer and Her Quest for Terroir